Great PowerBooks

by Charles Moore

The world of literature has its Great Books, sometimes referred to as the Western Canon. Apple Computer – now just Apple Inc. – has for the past 16 years produced another sort of ‘Book, prefixed by “Power,” “i,” and “Mac,” and some of them are pretty great as well, in a wholly different context.

Picking a short list of the greatest Apple notebooks ( or most anything else) always seems a bit presumptuous. It’s always to a large extent a value judgment, and my criteria for greatness may not always match yours. Pretty well every Apple notebook computer has had its loyal aficionados, even the much-maligned PowerBook 5300, which, fairly or not, is usually considered the nadir of the genre (ironically, its top-of-the-line model was also the most expensive Apple notebook ever made)

However, all Apple ‘Books have been great to varying degrees. There have been no really disastrous stinkers in my estimation, and I owned a PowerBook 5300. I liked mine a lot, and it was a good computer to me. My daughter still has that machine, albeit long retired, and at nearly 11 years old it still works.

Another PowerBook model that was widely regarded as less than wonderful was the PowerBook 150 – the last of the 68030 PowerBooks. The 150 was reliable enough, but with its lack of video output, no ADB port, and an oddball type of IDE hard drive, it was really not one of Apple’s better efforts.

Then there is the 600 MHz through 900 MHz G3 iBook which for reasons explained below, has earned a spotty reputation at best. I own one of those too, and mine has been a trouble-free performer for more than four years, so statistical probabilities don’t always bite.

On the other hand, my picks for Apple’s better portable efforts would include:

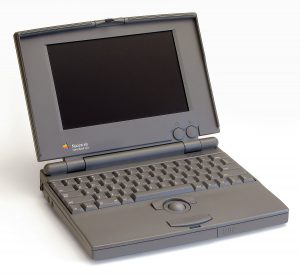

PowerBook 100

The great-granddaddy of them all, save for perhaps the 16 lb. Mac Portable, with which it shared basic internal engineering, the PowerBook 100, released in October, 1991, was a unique design, different from the other 100 series books. Built by Sony, the PowerBook 100 was not quite a sub-notebook at 5.1 lbs., but compared with its nearly 7 lb. stablemates, the 100 was a relative lightweight.

It was no ball of fire power-wise, with the 16 MHz 68000 chip from the Mac Classic and 2 MB RAM, expandable way up to 8 MB. The upside was that its sealed lead-acid battery gave it a running time of two to four hours between recharges.

The PowerBook 100 was also ahead of its time in being the first Mac ever without an internal floppy drive. You could order an optional external floppy for $200 over and above the base price of $2,500.

As for other aspects, the PowerBook 100 was pretty spartan, with a one bit (black and white — no grays) 9” passive matrix display of 640 x 400 resolution; a 20 MB hard drive; no sound; no expansion slots; and no video-out, but it did have a modem and a full-size keyboard.

Only in production for 10 months, the PowerBook 100 didn’t sell especially well, but it was appreciated by those who liked its unique qualities, and today is a collectible.

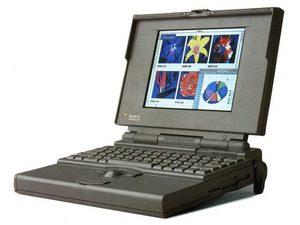

PowerBook 180c

The 180c wasn’t the first color PowerBook — that was the 165c — but it was Apple’s first really successful effort at building a color portable, and also, in my opinion, the most desirable 100 series PowerBook.

Its active matrix 10 inch, 256 color LCD display was a substantial improvement on the 165c’s murky little passive matrix screen. It also supported the then-standard 640 x 480 resolution instead of the scrunched 640 x 400 of previous PowerBooks.

The $4,160 180c, introduced June 7, 1993, was powered by a 33 MHz 68030 chip, with a math coprocessor, 4 MB of RAM and expandable to 14 MB, 2 Serial ports, an ADB port, a SCSI port, and a video adapter port. At 7.1 lbs., the 180c was no lightweight, and its NiCad battery had a miserable running life of only about one hour between charges, but it was a solid, decent-performing machine in the context of its time, with a display that needed no apologies.

PowerBook 500 Series

The PowerBook 500 “Blackbird” is one of the best-loved Apple portables of all time. It is was powerful for its time, stable, reasonably rugged, attractive in a swoopy sort of way, and held its value well. The PowerBook 500s were the first Mac laptops (except for the Duos in their docked mode) that could serve practically as one’s “only” computer — a true desktop substitute, albeit with some limitations.

The 500 series PowerBooks came in five models, with five different LCD displays, two clock speeds, and three versions of the ‘040 processor chip. The two slower 25 MHz units (520 and 520c) came with passive matrix grayscale and passive matrix color screens respectively. The faster 33 MHz 540 and 540c came with active matrix grayscale and color displays respectively, and the 550c, which was not distributed in North America, had a full 68040 processor (with floating point unit — the 520 and 540 models had FPU-less 68LC040 variants of the chip), a 10.4” active matrix color screen, and larger 500 or 750 MB hard drives.

All 500 Series models could support two NiMH “Intelligent” batteries( about 2.5 hours use each), and offered (rare) optional PC Card support in an expansion bay “cage.” Most came with an optional internal modem (Global Village “Mercury” — 19,200 bps). All versions featured a trackpad, full-size keyboards including function keys, a single serial port, stereo speakers, an internal microphone, video output, Ethernet, and a maximum RAM capacity of 36 MB. All were upgradable to PowerPC with a daughtercard swap-in.

The 500 Series PowerBooks are excellent computers that demanded few compromises when running the software of their era.

PowerBook Duo

The PowerBook Duo was another milestone ‘Book — the first compact subnotebook Mac Portable and the conceptual ancestor of the iBook.

The original Duo concept was for the laptop unit to serve as the CPU and hard drive core of a computer system that could slide into a docking station with a floppy drive (like the PowerBook 100, the Duo laptop didn’t have one) plus a full array of standard connectivity ports and two NuBus expansion slots, and connect to a standard CRT monitor. This was a lot more compelling in the days before large active-matrix color laptop monitors.

Despite being about 3 lbs. lighter than a full-size 100 series PowerBooks, the Duo was very robust, with a light but rugged magnesium chassis.

Duos, in a variety of configurations, actually had the longest model run of any Apple portable, being built from October, 1992 until April, 1996 — 3 1/2 years, thus surpassing the runner-up Titanium PowerBooks (two years, eight months) for production longevity.

The original Duo 210 and 230 had 25 MHz and 33 MHz 68030 chips respectively. They both had 9”, 640 X 400 passive matrix gray scale displays, and 4 MB of RAM expandable to a whopping (for the time) 24 MB.

The 210 and 230 were superseded by the Duo 250, with a 9” 16 gray scale active matrix display, and the Duo 270c –the first color Duo with its 8.4,” 640 X 480 active matrix display. Processor power and other specifications remained the same except that the 270c could support 32 MB of RAM.

In May, 1994, the Duos were upgraded again to 280 and 280c models, which were identical to their immediate predecessors except for having 33 MHz 68LC040 processors and a longer-lasting Type III battery that could go up to three hours between charges.

The last, and fastest Duo, the 2300c, was introduced along with the PowerPC PowerBook 5300 since September, 1995. Like the 5300, the Duo 2800c had a 100 MHz 603e processor, had the same 9.5” active matrix display used in the PowerBook 540c, came with 780 MB or 1.1 GB hard drives, and 8 MB of standard RAM upgradable to 64 MB.

Another new feature was a “tappable” trackpad that replaced the earlier Duos’ mini-trackball. At $3,700, the Duo 2300c wasn’t cheap, and because of an internal architecture inherited from the original 68030 Duos, it was even slower (by about 15%) than the none-too-speedy PowerBook 5300. It had also porked up to 4.8 lbs., about the same as the current 12” iBook.

PowerBook 1400

Some people refer to the PowerBook 1400 as the PB 5300 “done right,” which is probably a fair assessment. The 1400/117 is very similar internally to the much more expensive 5300ce, with a larger display and CD-ROM support, but several of the high end 5300 features missing. The 1400 happily proved to be solid in the several areas where the 5300 suffered deficiencies in ruggedness and reliability.

We have a couple of 1400s in the family, neither still in regular use, but they are reliable, nice-to-use machines with great keyboards.

Aside from the CD-ROM drive, there was little innovation in the PowerBook 1400. It had same two PC Card slots; a NiMH battery, 16-bit sound input and output; an infrared transceiver. The bigger 11.3” 800-by-600-pixel LCD screen with 16-bit-color support in both passive and active matrix is nice in both versions.

The PB 1400 included HDI/30 SCSI, ADB, serial (printer/modem), microphone, and external speaker, but in a nod to economy, no video-out port for an external monitor was included. An internal slot could accommodate video-out or Ethernet upgrade cards. Ethernet could also be supported with a PC Card, which was also the only choice for an internal modem.

The 1400 is no lightweight — about seven pounds with the CD-ROM drive installed, witnessing its solid construction. Three processors were offered during the 1400’s relatively long 18 month model run — all PowerPC 603e units in 117 MHz, 133 MHz, and 166 MHz clock speeds. The latter two included a 128k L2 cache.

One great advantage the PowerBook 1400 offered that the 5300 and later 3400 didn’t was upgradability; its processor resided on an easy-to-replace daughtercard. Both Newer Technology and Vimage offered a variety of G3 processor upgrades for the PowerBook 1400, but all were discontinued last year. However, Sonett Technologies now offers a G3 466 MHz upgrade card for the PB 1400, using a copper processor that extends the 1400’s battery life as well as supercharging its speed.

The PowerBook 1400 was designed for easy service access with its flip-up keyboard, and upgrade cards for this model offer straightforward installation. It takes only a few minutes to install the G3 upgrade.

However, it should be noted that a processor upgrade does nothing to address other 1400 limitations, like a slow internal system bus, 64MB maximum RAM capacity, and relatively slow video performance.

PowerBook 3400 Series

The PowerBook 3400 combined fast, new PCI-based motherboard architecture and faster 603e processors (all with 256k L2 cache) with a stretched version of the PowerBook 5300 case, to become, for a short while, the fastest laptop computer on the planet. The big, solid 3400 was plagued by very few gremlins and glitches, and is one of the most dependable PowerBooks of all time.

The PowerBook 3400 features essentially the 12.1” 600 x 800 resolution active matrix TFT screen still used in the clamshell iBook, a four speaker sound system, 16-bit video out, 16-bit stereo in/out, two PC Card slots, built-in 10Mbps Ethernet and an internal 33.6kbps modem (on all but the base 180 MHz model), and IR Talk infrared support.

There are three 3400 models, based on 180, 200, or 240 MHz 603e PowerPC processors with a 40 MHz internal bus. The 180 was and is the sleeper bargain of the bunch, commanding a substantially lower price but giving away relatively little performance-wise to its slightly faster siblings.

The 3400c’s expansion bay accepts a variety of modules, including a floppy drive, 6x and 12 x CD-ROM drives, and the LiIon battery provides decent running time between charges.

Despite its short-lived tenure at the top of the notebook heap, the 3400c represented a quantum leap in PowerBook performance, being up to three times as fast as the PowerBook 1400.

PowerBook G3 Series WallStreet

My workhorse Mac for 3 1/2 years was a PowerBook G3 Series WallStreet II 233 MHz, and it proved a more than worthy successor to my old 5300, and is still going strong in its eighth year of service, now my wife’s word processing, email, and Web-surfing machine. The original battery even stil holds a charge.

The WallStreet is arguably the most comprehensively complete and expandable PowerBook ever built, with its full set of classic PowerBook ports, two PC card slots allowing upgrades to USB and FireWire, or other things, its expansion day, the ability to support batteries in both the left and right bays, and the availability of processor upgrades to 500 MHz G4 power.

The WallStreet keyboard is regarded by many (including me – I like it better than any other keyboard I’ve ever used, period) to be the best keyboard ever offered on a PowerBook..

While they all look pretty much identical, there are six basic WallStreet configurations in two Series, two internal bus speeds, 5 1/2 processor speeds (233 MHz to 300 MHz), and four different screen options. They are all good machines, although some Series I models were equipped 13.3” active matrix display that often proved trouble-prone.

The most controversial G3 Series model is the Series I “MainStreet” 233 with its passive-matrix dual-scan screen and no backside cache. Some have accused this machine as being, quote: “dog slow.” It was not. The cache-less 233 MacBenched (4) at 445 in processor performance — one third faster than the previous “fastest-in-the-world” 3400c 240 (337). Nor is the dual-scan fast supertwist nematic (FSTN) screen as undesirable as some reviewers have implied. I find the FSTN display quite pleasant viewing, albeit not as crisp and speedy as the TFT units.

With their dual expansion bays, 83 MHz (Series I) and 66-MHz (Series II) internal bus, comprehensive set of ports, and big screens, the WallStreet was in its day a credible alternative to a desktop system in a portable package.

PowerBook G3 Series Bronze Lombard

The middle member of the PowerBook G3 Series troika — the PowerBook G3 Bronze or Lombard, looks virtually identical to its successor, the Pismo, but has the distinction of being the last Apple laptop to ship with a SCSI port instead of FireWire. Thinner and lighter than the WallStreet, the Lombard shed one of the latter’s PC card slots, and had only one removable device expansion Bay instead of two, but otherwise shared pretty much all of the WallStreet’s connectivity with the exception of having two USB ports instead of Serial and ADB ports.

The Lombard was available in 333 MHz and 400 MHz configurations — the latter of which came with a DVD drive. A 14.1” display was standard across the board, and the Lombard can be upgraded to 512 MB of RAM.

My son bought one of the last 333 MHz Lombards in the late winter of 2000, and it proved to be an admirably tough, reliable PowerBook. It runs OS X surprisingly well considering the modest clock speed, and the Lombard is also the oldest PowerBook that officially supports OS X 10.3 Panther.

PowerBook G3 2000 FireWire Pismo

My nominee for best Apple laptop ever isn’t even a tough choice. it would have to be the last, and best of the G3 Series triumvirate – the PowerBook G3 2000 FireWire, better known as simply the Pismo, introduced a Tokyo Macworld Expo in February, 2000.

The Pismo was a formidable machine from the get-go, as we will review in a moment, but even more remarkable is that more then seven years on, so many of them are still in active service. My own somewhat breathed-on example is a surprisingly lively performer running OS 10.4, albeit helped by a 550 MHz G4 processor upgrade and a 5400 RPM hard drive.

However, thanks to the Pismo’s expandability, mine has also been tricked-out with an 8x DVD-burning SuperDrive, a FireWire 800 PC Card adapter and a FastMac TruePower expanded capacity battery, and I also have SuperDisk and Zip Drive Expansion Bay modules that can be used when booted into OS 9, which the Pismo of course supports. It doesn’t quite match the WallStreet for versatility, having one fewer removable device expansion bay and PC Card slot respectively, but that is made up for substantially by its two FireWire ports and two USB ports. It can also support USB 2 with a PC Card adapter.

Another big greatness point for the Pismo is that it’s a reasonably rugged unit with fewer than average weak points an bad habits. Some of the OEM DVD-ROM drives were troublesomely short-lived, and there is the display backlight “pink screen” issue on high-hours units, but beyond that the Pismo has proved admirably robust.

All of which characterizes a truly great ‘Book, arguably the greatest so far.

With its UMA motherboard, 400 or 500 MHz G3 processors and 1 MB of L2 cache, Pismo was the fastest laptop on the planet in early 2000 — and amounted to substantially more than just a speed-bumped Lombard with FireWire substituted for SCSI and AirPort wireless support added.

The UMA mobo features a 100 MHz system bus makes the 400 MHz Pismo roughly 30% faster than a 400 MHz Lombard, thanks to the faster bus plus faster RAM and hard drives.

Pismo’s system software uses the ROM-in-RAM motif introduced to the PowerBook line with its Lombard predecessor. Called the “New World software architecture,” a small ROM contains the boot code needed to initialize the hardware and load an operating system. The rest of the system code that formerly resided in the Mac OS ROM is loaded into RAM with the system software from disk or from the network.

Pismo has two 400 Mbps bus-powered FireWire ports, that made SCSI PowerBook history, so Apple introduced FireWire Target Disk Mode as a substitute for the old SCSI Disk Mode. When a FireWire equipped ‘Book is in Target Disk Mode and connected to another Macintosh computer by a FireWire cable, the laptop operates like a FireWire mass storage device with the SBP-2 (Serial Bus Protocol) standard.

Pismo also has two 12 Mbps USB ports with UTA USB implementation and independent busses each USB port. The sound system for Pismo supports 44.1 KHz 16-bit stereo sound output and input, available simultaneously. Pismo was originally available with hard drives of 6, 12, 18, or 20 GB capacity, and supports PC100-compliant SO-DIMM modules and up to 512 MB of RAM. or even 1024 MB in two 512 MB modules, although there are some minor limitations that inhere with 1 Gig of RAM installed. Pismo has an ATI RAGE Mobility 128 Graphics Processor Unit with 8MB of SDRAM video memory that can support millions of colors on external displays up to 21 inches. Unfortunately, that’s very modest video support by today’s standard, and much of the time the biggest bottleneck to performance in OS X, as well as not supporting System 10’s Quartz Extreme, Core Image, and Core Video technologies.

However, in general the Pismo is one honey of a PowerBook, IMHO much preferable to its TiBook successor. I really like the one I’ve had for over going on six years now. For non-Altivec optimized software, the stock Pismo’s G3 processors give little if anything away to the Ti’s G4 units in performance. Pismo also has the aforementioned expansion bay, which the Ti doesn’t, two FireWire ports to the Ti’s one, and there is a case to be made for plastic being preferable to sheetmetal – even exotic sheetmetal – as laptop computer skin.

The Clamshell iBook

The original “clamshell” iBook, introduced in August, 1999, was, and remains, one of the most unique laptop computer designs ever. For one thing it was colorful. Previously all laptops had been black or gray (there was a very limited special edition PowerBook 170 in white), but the iBook came in arresting two-tone themes with bright colors –variously Blueberry, Tangerine, Indigo, Lime, and the more subdued Graphite — accenting Snow white.

The clamshell iBook had a carry handle, and it was sumptuously curvaceous rather than squared off. Not everyone liked the styling. It has been compared to a makeup compact and even a toilet seat, but it certainly wasn’t boring. The swoopy form factor also helped make the iBook’s Lexan case very rugged. The downside was that it was also big, bulky, and heavy — more so on all counts than its “ big brother” PowerBooks of the time.

Other iBook distinctions were that it had no doors covering the connection ports (a motif that is now universal on Apple laptops), and the spring loaded lid had no mechanical latches.

The first clamshell iBooks were modestly powered, with 300 MHz G3 processors, a miserable 32 MB of standard RAM, and a tiny 3.2 GB hard drive. They also were deficient in the port department, with just one USB port, Ethernet and modem ports, and a sound-out port. They were still great though for their revolutionary design innovations.

The last iteration of the clamshell iBook, introduced at Macworld Expo Paris in September, 2000, added FireWire connectivity and was available in up to 466 MHz of G3 power with a RAM limit of 320MB, either 10 GB or 20 GB hard drives, making the original iBook design a truly great laptop at last with no excuses. The only remaining caveats were a poky mono speaker and the 12.1” 800 x 600 resolution display is a bit cramped by today’s standards.

The 300 MHz iBook has the distinction of being the second-oldest Apple laptop officially supported by OS X 10.3 Panther (the Lombard PowerBook edges it by a few months).

The 500 MHz Dual USB iBook and The G4 iBook

You will note that the 600 MHz through 900 MHz G3 models are explicitly excluded from this white iBook family grouping. While they are nice machines when they work – I own an 51 month old 700 MHz example that has been a near flawless performer to date – the infamous logic board failure defect excludes these models from greatness, and in fact puts them in the running for the dubious distinction of being one of the worst Apple laptops ever.

However, the original 500 MHz Dual USB iBook that debuted on May 8, 2001, and which had essentially the same RAGE 128 Mobility graphics accelerator with 8 MB of VRAM that was used in the Pismo and the first generation Titanium PowerBooks apparently did not suffer an extraordinarily incidence of logic board failures. Ports include one 400 Mbps FireWire port, two USB ports, an Ethernet port for 10/100Base-T operation, and a built-in modem that supports 56ÊKbps data rate. The AirPort Card wireless LAN module is available separately as a user-installable option. There are two different video-out ports on the iBook, each requiring an adapter cable. The RGB output port supports VGA monitors and video mirroring but not monitor spanning. You can connect to regular monitors as well as RGB devices like projectors. However, if you want to use the AV out (Composite/RCA video) jack for connecting to a TV or VCR through an adapter cable or use your headphones in the same port (not simultaneously), you’ll have to purchase a $19 adapter from Apple.

The basic form factor, which eventually became the longest production life Apple laptop form factor, is about perfect.

In terms of footprint and styling, the dual-USB iBook most closely resembles the 5300 and its successor, the PowerBook 1400.

The Dual USB iBook was a radical departure from the previous clamshell iBook design, being square cornered and much smaller and lighter in form factor. It still had a 12” display, but with 1024 X 768 resolution — identical to the 14.1” displays and used in the G3 Series PowerBooks and the 14” iBook that came along in January, 2002, but with smaller pixels. It lacks a few features that are included in most PowerBooks, such as a PC Card slot, monitor spanning, and an analog sound-in port, but for the most part the Dual USB iBook is a worthy successor to the G3 PowerBooks.

Engineering wise, its biggest shortcomings are that the processor is not upgradable and it is a very difficult machine to open up and work on, even for something is prosaic as upgrading the hard drive.

The G4 iBook is not without its issues, but it proved much more reliable than the 600 MHz through 900 MHz G3 models. Applw piled a lot of PowerBook style features into the last, 1.33 GHz and 1.42 Ghz iBook G4 versions, making them an especially good value for the money value for the money. My daughter has a 1.2 GHz example, has travelled through much of Europe with it, and now has it with her in Japan

The 12” Aluminum PowerBook

It has been suggested by some that the 12″ aluminum PowerBook is a logical successor to the Pismo as the most desirable used ‘Book, and there is considerable substance to that argument, as the 12-incher’s amazingly strong resale value testifies now more than a year into the MacIntel era.

The 12″ LittleAl ‘Book represented one of the most convincing smash-hit model introductions in Apple history back in 1003. Sharing much of the general layout in engineering and the 12” display of the 12” iBook, the baby PowerBook added an aluminum housing and G4 Power, plus most (but not all) of

Another commonality with the Pismo is that the 12” PowerBook has proved more reliable than average. Its NVIDIA GeForce4 420 Go and NVIDIA GeForce FX Go 5200 graphics accelerators seem to be more robust than the ATI video cards used in the iBooks. Daystar also supports the 12″ PowerBook with G4 processor upgrades.

The 12” AlBook has the customary two stereo speakers plus a “midrange enhancing” third speaker. Its VGA video output supports dual display mode and video mirroring. The high-end LittleAl is equipped with a SuperDrive (DVD-R/CD-RW) optical drive.

The Little Al ‘Book is the smallest PowerBook ever built, although at 4.6 lb. it’s not as light as the original Duo 210, but it packs a powerful punch in a tiny package, with 867 MHz, 1 GHz, 1.33 GHz and 1.5 GHz G4 processors, a 133MHz system bus, and up to 1.25 GB of RAM supported. It also has the same full-size keyboard as its larger 15” and 17” aluminum PowerBook siblings.

The 17” PowerBooks

I had to include this one – the grandest PowerBook Apple ever built, with its gigantic 1440-by-900 or 1680 x 1050 resolution widescreen, 16:10 aspect ratio display. It’s not the most practical machine for serious road-warrioring, but it’s the ne plus ultra of of desktop substitute PowerBooks. I know; I use one as my main production workhorse.

With its aluminum alloy case, the big PowerBook is one inch thick, 15.4 inches wide. 10.2 inches deep, and weighs 6.4 pounds, making it the heaviest PowerBook since the WallStreet. That big screen, reasonable power in the PowerPC context, and a comprehensive inventory of connectivity and convenience features, the big PowerBook can definitely serve as a primary workstation with no excuses necessary.

The Big Al was and will remain the ultimate PowerPC Apple laptop ever, with up to 1.67 gigahertz of G4 power, support for up to 2 GB of RAM, a 167 MHz system bus,, Gigabit Ethernet, a DVD-burning Super drive, a high-speed FireWire 800 port, a backlit keyboard with ambient light sensor activation, Sudden Motion Sensor and a scrolling trackpad, and built-in Bluetooth for wirelessly connecting to cell phones and other Bluetooth equipped peripherals, and GPRS connectivity to check your email from anywhere.

The 17” BigAl ‘Book has proved to be admirably reliable, and it will be by virtue of its groundbreaking form factor likely to retain its “Great ‘Book” status in perpetuity.

Want to join the conversation? Comment below: