High-end PowerBooks - Living Large - Plus PowerBook Mystique Mailbag

by Charles W. Moore

I tend to be oriented toward the low end of the computer spectrum. It's not that I don't have appreciation for the finer things in life, but I also like to get the best practical value for dollars spent, and whether you look at that in terms of initial capital outlay or depreciation percentage, lower-priced systems almost always come out on top, provided they supply the requisite amount of computing power and features to satisfy your actual needs.

Over the past nine years I've owned four Apple laptops that have served as my main production computers, and all but one of them has been the lowest - priced model in their respective product families. The exception is my 2000 Pismo PowerBook, which was the meanest, fastest PowerBook ever made when it was new, but I got it used when it was a year old, and in that context it has represented possibly the best purchase value of all.

However, by the time any computer is three years old, it's just another old computer, and the distinction between top of the line and entry-level diminishes greatly. For example, my 500 MHz Pismo sold new for one thousand dollars more than the base 400 MHz Pismo, but today the 100 MHz difference in clock speed seems minuscule, and the difference in residual market value has shrunk to maybe $100 - $150. That's what I mean by best value for dollars spent.

Still, the high-end PowerBooks down through the years have been delectable machines, and of course were money no object, I would much rather have a PowerBook 540c than a 520, or a 292 MHz WallStreet instead of a 233 MHz unit with no L2 cache. The high-end jobbies are of course more desirable if you don't mind the fact that they typically depreciate like falling rocks.

So let's take a retrospective look at high-end PowerBooks past and present.

PowerBook 170

The PowerBook 170 was the first top of the line PowerBook model way back in 1991, the most expensive ($4600) of the three original PowerBook models.

For the $1,600 you paid over the price of the low-end PowerBook 140, you got a 25 MHz 68030 processor with a math coprocessor (floating point unit) rather than the 140's relatively puny 16 MHz '030 with no floating point unit, a built-in fax modem, and a crisp, black and white, active-matrix display in lieu of the 140's passive matrix screen. Actually, if you could budget the extra cost, you probably got half-decent value for your extra cash outlay with the 170, which was well-loved by its owners.

PowerBook 180/180c

The PowerBook 180 represented an even better value than the 170 when it came along in October, 1992, with its 33 MHz '030 chip (still with the FPU), it's maximum memory support raised from 8 MB to 14MB, a video-out port, and a nice, 10 inch, 16- level grayscale active-matrix LCD display -- all for a more friendly price of $4,100.

Nine months later, the PowerBook 180c took over as king of the hill, with essentially the same hardware specification as the 180, but a 10 inch, 256 color, active-matrix LCD display, and, amazingly, only a $50 higher price ($4,160) than the 180 had been introduced at. PowerBook 180s were also well loved by their owners. pix

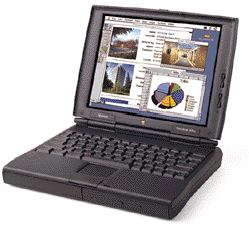

PowerBook 540c

In May, 1994, the 100 series PowerBooks were superseded by the futuristically-styled "Blackbird" 500 series, which initially included four models, the high - and version being the 540c, which had a 33 MHz 68LC040 Motorola processor and a 9-inch, 640 x 480 active-matrix color display. The 540c sold for $4,640, making it the most expensive PowerBook ever up to that point, and a whopping $2,370 more than the low-end PowerBook 520, which had a 25 MHz '040 and a 9-inch passive matrix grayscale display.

Was the 540c really worth more than twice as much as the 520, with which it shared an identical form factor and most other aspects? It depends on how much of a premium you put on having a color screen, but it's hard to justify in terms of performance. The other way to look at it is that the PowerBook 520 was an exceptional bargain at $2,270, since you got pretty much the same functionality at less than half the price of a 540c, and the lower demands of the grayscale display compensated substantially for a lower clock speed. My son had a PowerBook 520, and it was a great computer.

As a high-end footnote, there was also a PowerBook 550c that was sold only in Asian markets, with a 10.4-inch color screen and a full 33 MHz 68040 processor with math coprocessor (which the 68LC040 in the other 500 series models didn't have).

PowerBook 5300ce

The PowerBook 500 series was replaced in August, 1995, by the PowerBook 5300 family -- the first ever PowerPC Mac portables, and, as it would turn out, the PowerBooks with the most checkered reputation.

Top of the line was the PowerBook 5300ce, which at a suck-in-your-breath $6,500, has the dubious distinction of being the most expensive PowerBook ever, and a whopping $4,300 more than the entry level PowerBook 5300 that sold for $2,200.

The punch line was that both of these computers shared the same form factor, motherboard architecture, keyboard, and case plastics. For that extra $4,300 what you got was a 17 percent faster 603e processor (117 MHz vs 100 MHz), a very nice 10.4-inch 800 x 600 active-matrix display instead of a 9.5-inch passive matrix grayscale unit, a 1.1 gigabyte instead of a 500 MB hard drive, and standard 32 MB instead of 8 MB of RAM. Nicer to have as these enhancements were, they didn't even come close to justifying the extra purchase tariff in rational terms.

I bought a base 5300, which was also the fastest 5300 thanks to the lower power demands of its murky little grayscale screen. It was my first PowerBook, got me hooked on portable computing, and I figured it was a bit of a bargain compared with the 5300ce at nearly three times the price.

PowerBook 1400c

The PowerBook 5300's troubled tenure ended after 13 months, to be replaced by the PowerBook 1400, which was not a radical departure in size or form factor, and had the same 117 MHz 603e chip as the 5300ce, but turned out to be one of the most solid, reliable PowerBooks ever.

There were originally just two PowerBook 1400 models, both with 11.3-inch color displays, the main distinction being passive or active-matrix. The high-end model was the $4,000 1400c, which cost $1,500 more than the passive matrix 1400cs. Eventually, over its long production run, you could get the 1400 with 133 MHz or 166 MHz 603e processors, these two higher clock speed units also having a level 2 cache which boasted performance more than the nominal clock speed increase would imply.

The PowerBook 1400 also had its processor mounted on a removable daughtercard, which facilitated processor upgrades that extended the life of many PowerBook 1400s into the the G3 era.

PowerBook 3400c/240

The PowerBook 1400 was one of the best-loved Apple 'Books ever, which may have been why it was kept on as the entry-level PowerBook when the PowerBook 3400c was released in February, 1997. The 3400 itself came in three models, distinguished mainly by clock speed and hard drive capacity.

The high-end PowerBook price soared once again into the stratosphere, with the 3400c/240 going out the door for $6,400 -- just one hundred dollars less than the PowerBook 5300ce's all-time record, but offering a lot better value for the cash outlay.

With the 1400 (and later also the subnotebook - sized PowerBook 2400) still around holding down the bottom end, the "base" PowerBook 3400c/180 was no cheapie at $4,500, but since all the 3400s had the same 12.1-inch 800 x 600 active-matrix display and PCI motherboard architecture, it was a relative bargain compared with the $1,900 more expensive 3400c/240.

PowerBook G3 (3500, "Kanga")

The PowerBook 3400c/240, which was touted as "the fastest laptop on the planet," had a very short tenure as king of the hill, displaced for that honor just eight months later by the first ever G3 PowerBook, imaginatively named the PowerBook G3, with a 250 MHz G3 processor but otherwise almost identical to the 3400c.

The "Kanga" as it was also known, sold for $5,700, and PowerBook 3400c prices were reduced accordingly. It turned out to be a short production life model made for only five months.

PowerBook G3 Series WallStreet 292 and 300 MHz

In May, 1998, the PowerBooks G3 ,3400c, 2400c and 1400 were all discontinued, and replaced by the PowerBook G3 series, with a completely new form factor and a comprehensive array of models contained within it, ranging from a 233 MHz budget machine with no level 2 cache and a 12.1-inch passive matrix color display at $2,300, to the top of the line 292 MHz model with a 14.1-inch active-matrix screen at $5,600.

Once again, low end purchasers of the base, "MainStreet" model benefited greatly from engineering and componentry shared across the model spectrum, but in this instance you at least got a substantial increase in performance for your extra $3,300 if you went for the 292 MHz model.

Four months later, the G3 Series was overhauled, with the low-end 233 MHz model getting a 512k level 2 cache and a 12.1-inch active-matrix screen, and the high-end model boosted 8 MHz in clock speed to 300 MHz, but with a slight diminishment in performance, since the second-generation machines were reduced from 83 MHz to 66 MHz bus speed.

I replaced my PowerBook 5300 with one of the second-generation 233 MHz WallStreet models, and I'm still using it for light duty tasks nearly seven years later. The high-end WallStreet models were definitely desirable pieces of work, but I'm still not convinced that they were enough nicer to justify the higher cost of entry.

PowerBook G3 Bronze (Lombard) 400 MHz

Exactly one year after the WallStreet's release, it was replaced by the new PowerBook G3 Bronze, better-known as "Lombard," which came in just two models, with 333 MHz and 400 MHz G3 processors respectively, sharing the 14.1-inch display carried over from the WallStreet. While the Lombard's styling was derivative of the WallStreet, the case plastics were entirely new, with a much slimmer profile and lighter weight.

The elimination of a really low end PowerBook model was facilitated by the July, 1999, introduction of the iBook consumer laptop, and the difference between the two Lombard models boiled down to 66 MHz of clock speed, 512k more L2 cache in the 400 MHz unit, hard drive capacity, and a standard DVD ROM drive in the 400 MHz model, which at $3,500 sold for $1,000 more than the Lombard 333.

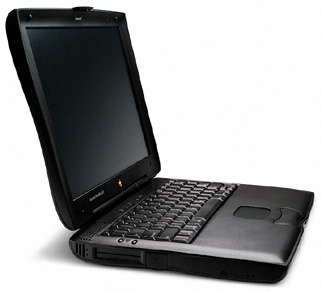

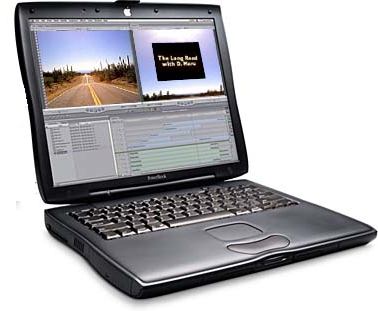

PowerBook G3 FireWire 500 (Pismo)

The last of the G3 PowerBooks, best known as "Pismo," came along in February, 2000. In appearance it was almost identical to the Lombard except for having two FireWire ports instead of an HDI 30 SCSI port, but under the skin it was quite a different animal, with a 100 MHz system bus, support for PC 100 RAM, a substantial motherboard architecture overhaul, and ATI RAGE Mobility 128 video support.

The two -model lineup and respective price points were carried over from the Lombard, with the $1,000 dollar gap even harder to justify, since both versions shipped with the same DVD ROM drive, had 1 MB of L2 cache, and were only differentiated by 100 MHz of clock speed, hard drive capacity, and standard RAM.

The Pismo shares honors with the PowerBook 1400 as being the PowerBook most hospitable to processor upgrades, and in that context the 400 MHz model is a better value.

I love my 500 MHz Pismo, (now with a 550 MHz G4 upgrade), but I doubt that it was worth the price premium over a Pismo 400 when it was new.

PowerBook G4 Titanium 500 MHz, 667 MHz, 800 MHz, and 1 GHz

The PowerBook G4 Titanium had the longest production run of any PowerBook ever, and was offered in four distinctive two-model families. The original "Mercury" models in January, 2004 retained the Pismo's 400 MHz and 500 MHz clock speeds, but now with G4 chips, and much of the Pismo's relatively fresh motherboard engineering. The machines sold for $2,599 and 3,499 respectively, and for your extra $900, you got 100 MHz more clock speed, 128 MB more RAM, and a 50 percent larger hard drive.

With the "Onyx" refreshments released in October, 2001, the distinction between the two models opened up a bit. The entry level machine was essentially a carryover "Mercury" with a 50 MHz speed bump from the previous 500 MHz model, but the 667 MHz version got a 133 MHz bus while the 550 MHz unit retained the 100 MHz bus of the previous PowerBook G4. The 550 MHz model came with 128 MB of RAM while the 667 unit came with 256, and The low end unit had a 20 GB drive while the high end sported a 30 GB drive.

Big news was that the price points had shrunk to $2,199 and $2999 respectively, and given the significant disparity in performance, this may have been one case where the high-end machines offered the greatest objective value, with a price premium of just $800.

The "Ivory" TiBooks that came along in April, 2002 got another substantial makeover, with the 667 MHz model becoming the low end, and a new 800 MHz machine at the top of the line. There were also new higher resolution displays, with 1280-by-854 pixels, 23 percent more than previous models, along with higher brightness and better color saturation, and an ATI Mobility Radeon 7500 with 32MB of DDR SDRAM to support them.

Unfortunately, prices also crept higher again, to $2,499 and $3,199 for the two models respectively, but the gap between low-end and high-end actually shrunk another hundred dollars to 700 dollars, for which you got twice as much standard RAM and a 33 percent higher capacity hard drive

The final iteration of the TiBook, in November, 2002, boosted clock speeds to 867 MHz and 1 GHz. Video support was upgraded again to the ATI Mobility Radeon 9000, and integrated 802.11 wireless networking was included, With price points back down to $2,299 and $2,999 — still a $700 difference, but in this case you got 133 MHz more clock speed. twice as much video RAM, a 33 percent higher capacity hard drive, a pre-installed Airport card, and a DVD burning SuperDrive instead of a combo drive, making the ultimate TiBook one of the better values with respect to high-end over low end.

PowerBook 17 Inch Aluminum

Which brings us to the current King of the PowerBooks, which has been with us since January, 2003, in a consistent form factor with a humongous 17-inch, 1440 x 900 display, and has been offered in 1 GHz, 1.33 GHz, 1.5 GHz, and 1.67 GHz clock speeds.

The 17-inch PowerBook has been a single-spec model (with some build to order options) from the beginning, the $3,299 price of the original GHz machine having eased to $2,699 with the current 667 GHz model.

The BigAl has tempted me more than perhaps any other high-end PowerBook model because by historical standards you get so much more for your money in a top of the line PowerBook ever. My low-end PowerBook WallStreet 233 MHz listed for Can$3,595 back in 1998. The 17-inch PowerBook today sells for Can$3,489. The enhanced value equation is obvious.

But the thing is, you can also get a 1.2 GHz iBook for Can$1,249, or in US dollars the price spread between the cheapest Apple laptop and the king of the hill PowerBook is still $1,700 — nearly three times as much.

It's arguable that the extra value for the money is there in this case, if you can afford it, but it remains a judgment call.

PowerBook Mystique Mailbag

Your Good Insight

From Robert Tanis

Hello Charles,

During the past few years I have read a number of your thought-provoking articles (dare I say blogs) which deal with the Mac Laptops and associated OS and software.

Today I happened to read, at different times, three new Charles Moore articles and this caused me to realize your important position in the Mac community. In my mind you are extremely knowledgeable about Mac laptop technology, have a great way of explaining it to the less technical user and are passionate about powerbooks and iBooks. There is, to my knowledge, no other person more qualified for what I propose.

Years ago I moved away from Mac workstations to the portable line - totally and completely. Best move (most productive) I ever made. These tools (software and hardware) have become very important to me in supporting my work. Tried seriously to work with the pc, but it was a no go. So these days I use a new 12 PB with SD and 768 RAM (and here is an aside - using and understanding Activity Monitor I think 768 is sufficient for me {InDesign CS2, Canvas 8, Office, Safari and Apple Mail}). And another aside - the keyboard it terrific as is the video capability (having DVI capability to drive my 23 inch Apple HD monitor at home is important as well). All my other PBs (new 15" and new 17") are in hibernation.

Anyway, I digress. The book Derrick Story wrote was a start, but really did not include sufficient detail (and even now it is out-of-date). My belief is that we need a detailed capture of just what life was like with the 68000 and forward laptops. But in addition, a detailed treatment of accessories and mods. Which are good and why. Some explanation of how to take apart a Powerbook (iBooks are tough) and who provides excellent repair services. This is the kind of stuff you do well and it only needs to be coalesced into a single source. Make it an e-book if that is easier, but seriously think about my suggestion.

Thanks for your time.

Robert Tanis

Hi Robert;

Thank you for your comments and for your kind words about my scribbling. what facility I have for explaining Mac laptop technology to less technical users is largely by default, since I would not characterize myself as being any sort of technical expert. Just a relatively well informed and somewhat experienced user myself.

Thanks also for the great report on the 12-inch PowerBook. I'm fascinated that you have both 15 inch and 17-inch machines available, and prefer to use the little one instead. My personal tastes also tend to favor smaller machines.

Actually, I have pitched the idea for a PowerBook book of the sort you suggest to several publishers over the past couple of years, but have had a lukewarm response. It has been suggested that there is not the broad enough market appeal. I disagree, but am pretty much run ragged with existing commitments and haven't had the time or energy to pursue such a project on spec. Hopefully, the way will open up some time in them in the future.

Charles