In The Beginning - The Dawn of the PowerBook

By Charles W. Moore

I came to the Mac orbit in 1992, missing the advent of the PowerBook by just one year. At the time, PowerBooks seemed like exotic machines, astronomically expensive and more likely to be used by stars and celebrities than me ordinary mortals -- or so it seemed to this owner of a used Mac Plus.

There was something about the PowerBook, even regarded vicariously, that just grabbed you, or at least it grabbed me -- a quality I've come to call the "PowerBook mystique." Derrick Story describes it well in the cover blurb of his new "PowerBook Fan Book:" "Is it a computer or a work of art? The Power Book is both -- the most beautiful laptop in its class, with performance rivaling any challengers... The PowerBook represents the perfect union of form and function.... the pinnacle of Apple engineering....

"But there's another tantalizing trait that is seldom covered in magazine articles or online reviews. It's the PowerBook's ability to bond with its owner. For many folks, the PowerBook becomes an extension of their own thinking, helping them to remember important information, organize their work, and even manifest their creative vision."

Well said. Derrick is talking in particular about the current ecurie of aluminum PowerBooks, but the observations apply essentially to any PowerBook (or iBook for that matter) since the beginning 13 years ago.

Apple's wonderful PowerBook, which debuted in October 1991, wasn't the first portable computer, or for that matter even the first portable Macintosh.

Some computer historians consider the first true portable computer to be the Osborne 1 introduced by Osborne Computer in 1981. This 24 pound behemoth weighed seven pounds more than the compact desktop Macintosh that debuted three years later. The The Osborne 1 cost $1,795.00. came with a five-inch screen, modem port, two 5 1/4 floppy drives, some bundled software programs, and a battery pack. It was not a sales success.

In 1983, Radio Shack released its TRS-80 100, a 4 lb. battery operated portable computer that vaguely resembled what was to become the generic laptop form factor. A refined, upgraded, and smaller TRS 200 was released in 1986.

Compaq Computer introduced a laptop PC with VGA graphics — the Compaq SLT/286 — in 1988. NEC followed in 1989 with the 5 lb. NEC UltraLite — considered by some to be the first real PC "notebook style" computer.

The eponymously named Macintosh Portable, a 16 pound "luggable" computer, was rolled out in September, 1989. The Macintosh Portable did not share the classic laptop form factor, being essentially a foldable version of the contemporaneous Macintosh Plus and SE desktop machines, which it weighed only a pound less than. It's heavy weight, and heavyweight price ($6,500), prevented it from ever becoming a big seller.

In March 1991, Microsoft released the Microsoft BallPoint Mouse that incorporated both mouse and trackball technology in a pointing device designed for laptop computers. Then in October of that year, Apple Computer released the Macintosh PowerBook 100, 140, and 170, which came with trackballs.

The 1991 PowerBook would become the paradigm-setter for all laptop computers -- Mac and PC -- for the next 13 years and counting. Features pioneered by the first 100 Series PowerBooks on 1991, and introduced or popularized in PowerBooks and iBooks since then, have become the de-facto standards of the industry -- things like keyboard palm rests, the integrated trackpad, and the basic physical configuration shared by most laptop computers nowadays.

But we're getting ahead of ourselves. With a 16 MHz 68HC000 processor (a low-powered version of the Motorola 68000 processor chip) and a maximum RAM capacity of 9 MB, the Portable was a higher-powered machine than either of its desktop progenitors, and its 9.5-inch one bit (black and white) active-matrix LCD display (backlit on later versions) at 640 x 400 pixel resolution displayed more information that mean 9-inch CRT monitors in the original desktop Macs.

On one aspect -- battery life -- the Mac Portable was ahead of its time. It's rechargeable lead-acid battery could provide about five hours running time, performance not matched in Power Books and iBooks until the introduction of lithium ion batteries in the late 90s, and still in the same ballpark as the most power- parsimonious iBooks.

The Apple learned quite a bit from the Macintosh Portable experience, and applied the lessons to the design of the PowerBook, a project that was actually farmed out to Sony, whose engineers took the Mac Portable design and miniaturized it, while retaining the Mac portable's motherboard architecture and ROM, while whittling it down to a much more reasonable 5.1 pounds.

To help keep weight down, the PowerBook 100, as it was called, had no internal floppy drive but just a 20 MB hard drive, which was a respectable capacity for the day. An external floppy drive was a $200 option, over and above the basic price of $2,500. The PowerBook 100 case was made of lightweight molded plastic rather than the polycarbonate used in later PowerBooks and iBooks, and it had a lead-acid battery that provided about two hours running time, or a bit more with power conservation techniques.

The PowerBook 100 had a 9-inch passive matrix 640 x 400 1-bit display and came with two megabytes of RAM, expandable to a maximum of eight megabytes.

One another characteristic of the PowerBook 100 shared with the Mac Portable was that it didn't sell very well. The slightly heavier, more expensive, but fuller-featured and more rugged PowerBooks 140 and 170, introduced simultaneously with that PowerBook 100, proved more popular, and the 100 was only built for ten months, with the price being a radically slashed toward the end of its run to as low as $700, making it the least expensive Mac portable model ever, essentially when adjusted for inflation.

While the PowerBook 100 shipped with Mac System 7.0.1 installed, it would unofficially boot from System 6.0.7 and 6.0.8, making it the only PowerBook that can run System 6 (which used less battery power than System 7). The PowerBook 100 also pioneered SCSI Disk Mode, which allowed the PowerBook to function as an external SCSI device for other Macs, but was not supported by the 140 and 170 models. This function lives on today as FireWire Target Disk Mode.

The PowerBook 100 had a devoted coterie of fans, but it was really the bigger, heavier, and more expensive PowerBook 140 and 170 that set the template not only for Apple portables, but for the entire category of notebook computers of all OS platforms.

The "big" original PowerBooks included most of the basic features of the PowerBook 100, and added stereo sound-in and out with a built-in microphone, an internal floppy drive, bigger displays, and a full array of ports.

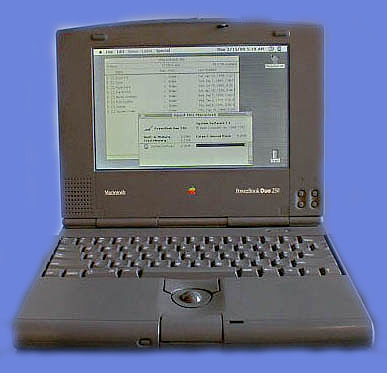

Another paradigm-setter in the early PowerBook family was the Duo, which established the modern subnotebook category and can be regarded as the ancestor of the 12" iBook and the 12-inch PowerBook, although it was a premium-priced model way back then.

While the full-size 100 Series PowerBooks weighed about seven pounds, a little Duo tipped the scale at a svelte 4.3 pounds -- still the lightest Apple laptop ever. The Power Book 140-180c form factor measures 2.25" x 11.5" x 9.6", whereas the Duo was a trim 1.42" x 10.87" x 8.5 inches. For comparison, a 12-inch aluminum PowerBook measures 1.18" x 10.9" x 8.6" (extremely close to the original Duo dimensions) and weighs 4.6 pounds. A characteristic the Duo shares with the current iBooks is its internal magnesium frame for rigidity combined with lightness.

However, unlike the iBook, the Duo had an undersized keyboard and a tiny marble-sized trackball 19 millimeters in diameter (compared with the 31 millimeter trackball in the 100 Series PowerBooks). One characteristic I liked about the Duo keyboard was its short travel -- about 2.5 millimeters instead of the three millimeters of PowerBook 100 Series keyboard.

The Duo also pioneered the use of nickel metal hydride (NiMH) batteries instead of the 100 Series' slow-charging and relatively short-lived nickel cadmium (NiCad) units. NiMH batteries also were used in the PowerBook 500, 5300, and 190 models before being displaced by with the Lithium Ion (LiIon) units in the PowerBook 3400 and later models. The NiMH battery can recharge in about an hour and a half, compared with 4-5 hours for the NiCad cells used in the PowerBook 100.

The reason Apple engineers were able to keep the Duo so light, without sacrificing ruggedness, was that they left out most of the I/0 ports and the floppy drive. For connectivity and expandability you needed a Duo-Dock -- a desktop computer-sized box that literally swallowed the Duo laptop module turning it into the processing guts of a desktop computer with a full array of ports, two NuBus expansion slots, better video and sound support, and so forth. If you're docking needs were more modest, you could opt for a Mini-Dock, which weighed 1.5 pounds and just added the standard array of I/0 ports. There was also a Duo floppy adapter, which allowed connection of an external floppy drive and had an ADB port for connecting an external mouse and keyboard.

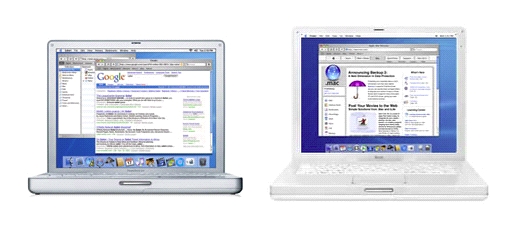

All this was quite ingenious, but I think that the design of today's 12 inch iBooks and PowerBooks, which come with a full array of ports and an optical drive built-in, is much more elegant and more than justifies the additional half pound or so of weight. Don't you agree?